“Il scopo del gioco è tirare la pallina e colpire i paletti, e gli avversari con la mazza in mano, deve invece, devono evitare che la palla colpisca i paletti e colpirla il più forte possibile e correre da una base all’altra. (The objective of the game is to throw the ball and hit the stumps, and the opponents, with bat in hand, must prevent the ball from hitting the stumps and hit it as hard as possible and run from one base to the other.)”

As the Italy players celebrated their historic win, possibly thinking of what the future held for them, in the stands sat their past. Watching the match in Mumbai were Francis Jayarajah and Simone Gambino, the founders of Associazione Italiana Cricket, now known as Italian Cricket Federation, in 1980.

For Gambino, the win was about the genuine exposure of the sport to an Italian public that had previously been only dimly aware of its existence: “It’s like the unearthing of a new reality for the Italian public, who certainly had no to very little awareness of cricket. Now they know it exists.”

The buzz, he said, was not only because of the result against Nepal, but from the team’s composition itself – Australian players of Italian heritage, complemented by players from the subcontinent who now live in Italy. For the first time, the tournament was also broadcast live in Italy on Sky, with commentary in Italian, and journalists from Italian papers were sent to cover the team at the World Cup. Visibility, one of the sport’s greatest hurdles, was finally being addressed. “Plenty, plenty of buzz back home,” Gambino says. “And by now, the snowball is rolling on its own.”

For Jayarajah, now 78, watching history unfold at the Wankhede Stadium still feels unreal. “I never thought that we would arrive here. Getting into the T20 World Cup felt like a miracle, to thrash Nepal is a whole other thing.”

Jayarajah arrived in Italy from Jaffna in Sri Lanka in 1968 to study mathematics at the University of Rome. He soon started playing cricket with expatriates at the British and Australian embassies, whose teams used to play the Rome Ashes, with the games usually taking place in the park of a villa owned by Princess Orietta Doria Pamphilj and her husband, Admiral Frank Pogson.

Back home in Jaffna, he had played college cricket, though never professionally.

In Italy, football was inescapable, especially in the era of Gigi Riva and Gianni Rivera, names that dominated sporting conversation. “Everyone back home used to say in Italy you would play football,” Jayarajah says. “In fact, it was like that when I came there – they were talking about Riva-Rivera, but I managed to put cricket in the middle.”

While working with the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations, his days were divided between office hours and net sessions. He worked from 8am to 6pm, then practised from 6.30pm to 8.30pm, the schedule – full-time work followed by cricket – that is familiar to many Italy players even today.

And many years later, Gambino and Jayarajah’s paths converged. Raised in Italy by American grandparents, Gambino discovered cricket during his summers in England and watching expats playing in parks in Italy in the 70s. “There was this private ground in Rome Park, where Francis used to play, and as a young kid, I went there and watched the game. And that’s how it started.”

“I often explain cricket in baseball terms to the parents because obviously, baseball, even though it’s not very played in Italy, it’s shown on TV, [like] American films. So we know a bit about baseball. But I say baseball is boring, and cricket is fun – that’s how I put it”

Leandro Jayarajah

Gambino’s love for cricket made him want to expand the game in the country. “Cricket was at the time just an expatriate activity, which was dying because the English just wanted to have a game and leave, they weren’t interested in bringing cricket to Italy. And I thought we had to bring in the Italians to play.”

Jayarajah and a group of friends had established the Doria Pamphilj Cricket Club, playing out of the villa grounds that had long hosted expatriate matches. After the federation was launched in 1980, Jayarajah captained Italy on their first tour of the UK in 1984.

The name of the club changed to Rome Capannelle Cricket Club in 1983 when they moved to its new – and current – ground, inside the Capannelle Racecourse along the Appian Way.

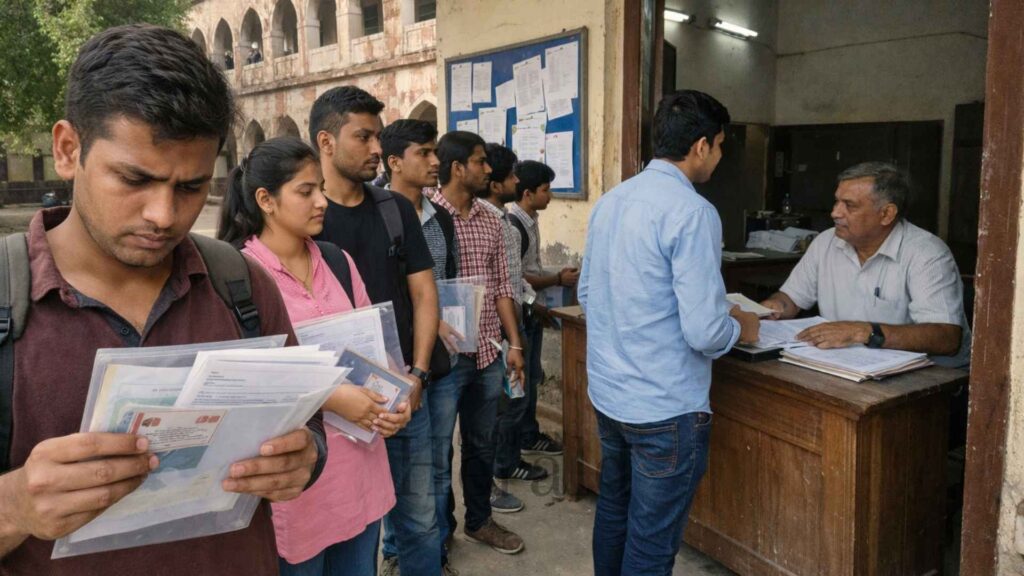

But setting up the club was not straightforward by any means and was met with scepticism, Gambino says. They also tried integrating Italians into the teams, introducing a rule mandating seven Italian players per side. “Every summer, hundreds of thousands of Italian students used to go to England on holidays. So most of them got in contact with cricket. And through these, we grew up the first generation of about 200 genuine Italian cricketers,” Gambino says.

Roma Capannelle remains one of Italy’s oldest running clubs, with age-group and senior cricket taking place across genders. From the current team, Anthony Mosca and Crishan Kalugamage were previously part of the club. Leandro, who once played for Italy himself, now coaches and runs the organisation. He sees growing interest among Italian children, even if parents remain unsure.

“I often explain cricket in baseball terms to the parents because obviously, baseball, even though it’s not very played in Italy, it’s shown on TV, [like] American films,” Leandro says. “So we know a bit about baseball. But I say baseball is boring, and cricket is fun – that’s how I put it.”

Women’s cricket, largely driven by the Sri Lankan expat community, has developed steadily since the 2000s. Leandro points to a lesser-known chapter in Italy cricket: the formation of a women’s team at a secondary school in the small town of Treviso.

“An Italian, Rosy Giunta, was so fond of cricket she had a Sri Lankan coach. In 2007, that led to the establishment of the first cricket club of Treviso in Casteller Secondary School, it went by the name Olympia Castellar. The project went really well but unfortunately then when the cricket grew to 40 overs, they had a bit of a drop out,” he says.

Roma Capannelle also fielded a senior women’s side, largely made up of partners and family members of the men’s players, and they went on to win two Italian titles of their own. “Women’s cricket is still going strong. The numbers are not as high but the standard is really good.”

Even today, facilities remain the biggest constraint. “When you compare cricket to football, basketball or other sports, obviously not having facilities, it’s hard to get Italians involved in the game,” Leandro says. “It’s a summer sport. It’s very hot in Italy, and it’s hard for a family to take a kid for seven hours on the ground compared to going to the beach.”

Yet, despite the logistical hurdles, he sees enthusiasm in the players themselves. “I’m sure Italians do love the game; they pick it up really quick,” he says.

Also – a bit of a historical irony – did you know that prominent football clubs such as AC Milan and Juventus, as well as Genoa CFC, began as cricket-and-football institutions before switching their focus to football-only? That first “C” in “Genoa CFC” stands for cricket. AC Milan began in 1899 as Milan Football and Cricket Club. Juventus was a multi-sport club.

However, there have been barely any attempts to revive cricket at those clubs.

“It is an activity which does not fall into the Italians’ DNA… add to this the fact that we don’t have the infrastructure,” Gambino says. “I think we are the first country playing a World Cup that doesn’t have grass wickets. And the culture of the game is very, very weak. And whilst you can build grounds, coach players, instruct umpires and scorers, the creation of a culture is something that takes much longer.”

All roads now point toward the Olympics, where cricket’s reintroduction could prove transformative, Gambino and Leandro say, a sentiment echoed by the current team coach John Davison, the former Canada international. “The World Cup is big but the Olympics are going to be even bigger. Even if Italy are not playing, being shown on TV is going to be massive,” Leandro says. “The Olympics is where Italians will finally see cricket as an international sport and that hopefully brings lots of Italians into the game.”

For now, cricket in Italy still remains a project sustained by pure passion, by people who train after long office hours, by expats who carry the game across continents, all in a team tied by multicultural threads.

Sruthi Ravindranath is a sub-editor at ESPNcricinfo